Well, college football is now even more broken than it was before this week. Colorado, Arizona, Arizona State, and Utah are headed to the Big 12, Washington and Oregon are headed to the Big Ten, and the remaining Pac-4 are looking for a last-ditch lifeline to avoid falling out of the power conferences entirely.

It’s pretty bleak, considering that before all this nonsense went down, the Pac-12 was such a paragon of good alignment amid the chaos in other conferences. Where other leagues locked in annual games like Texas A&M–South Carolina and Minnesota-Maryland, this one had two obvious divisions and was comprised of six obvious rivalry pairs. (Well, five pairs and Colorado/Utah, which was good enough.) Fittingly, the destruction of such a geographically and historically pleasing conference has now led directly to a world where teams in Orlando and Salt Lake City are both part of the same league.

The Pac-12 required little maneuvering to come up with an excellent, logical scheduling arrangement. The Big 12—or, as we’ll call it going forward, the Big XVI—has it quite a bit tougher. There are certain advantages conferred by the collection of teams at hand: sixteen is a fairly malleable number conducive to a variety of setups, and there aren’t a great number of rivalries that demand protection. Yes, there will be cross-country treks like Arizona-Cincinnati or BYU-Houston, but as long as the conference plays its cards right, they can come up with an alignment that works pretty well for everybody.

So, what’s it gonna be?

Protected Rivalries

College football has been moving towards protected rivalries for a while, and with the Big Ten officially making that leap (before adding Oregon and Washington, which makes a bit of a mess of things), the floodgates seem to be open. It’s a practical solution in a lot of ways, especially if you can manage to find some wiggle room in how many locked-in games each team has, exactly.

The Big Ten hasn’t made it fully clear how they plan to do that while keeping schedules balanced, though, and it’s even less obvious now that they’re adding two more members. For the sake of this study, we’re going to give everybody the same number of annual opponents, which makes the selection process a bit trickier but the mathematics in the end a lot nicer.

One protected rivalry for each team almost works. There are a lot of semi-important games that would become non-annual, like Texas Tech vs. Baylor or Colorado vs. Utah, but those are fairly minor sacrifices considering how elegant a system this would be, especially given that they would still be played every other year. One team, though, ruins everything: Kansas State. The Wildcats are the only team in the league with two must-have in-conference rivalries—their in-state duel with Kansas and the Farmageddon game against Iowa State. Both are among the longest continuous series in the sport, and skipping either for even a single year would cause riots in the streets. So, as nice as this would be, it’s a non-starter. Besides, whoever you pair KSU with, the team left out has to provide Colorado with a partner, which is pretty weird in either case.

Well, if one rival per team doesn’t work, surely two will do, right? Adding to those from the first map, this lets us lock in some of those minor games as well as Farmageddon, which is generally a lot nicer. However, we’re gonna have to start making some rather odd choices for annual games whatever way we slice it. Here, I’ve prioritized adding the most important rivalries missed above, which means KSU-ISU, Colorado-Utah, and Baylor-Tech all make the cut. But this causes some geographic awkwardness, leaving three teams way out west, three way out east, and four right in the middle. Two of those central teams, Oklahoma State and Kansas, have to give distant opponents a pairing, leaving them unable to link up with each other despite the mere four-hour distance from Stillwater to Lawrence. At least everything’s protected, but the real problem is scheduling: rotating through 13 non-rivals for every team would be a massive headache, making it nigh impossible to remember who you’re slated to play next season.

A third locked rival, while unnecessary for basically everybody, does alleviate that scheduling issue. Thanks to the lack of additional games that demand inclusion, we can go a lot more geographic this time, which should make travel less of a hassle as well. The main question is whether to pair Texas Tech with Arizona or Houston, both historical rivals they’ve been split from for a while. To avoid any awkward permutations with the five western schools, I’ve chosen the former, but it wouldn’t be all too difficult to get the Red Raiders and Cougars together. Plenty of weird games would become annual under a system like this, no matter what particular “rivalries” are chosen, but scheduling would be a breeze: three locked rivals, then a two-year rotation through the other twelve opponents for a nine-game schedule.

Pods

Thing is, protected rivalries are boring, and they’re not really the best solution for the Big XVI in particular, with so few must-have games between its odd collection of teams. If this league wants to set itself apart from the Big Ten and SEC, the least it can do is not copy their homework on alignment, right? So, why not take an idea that both of those conferences spurned and see what they can do with it?

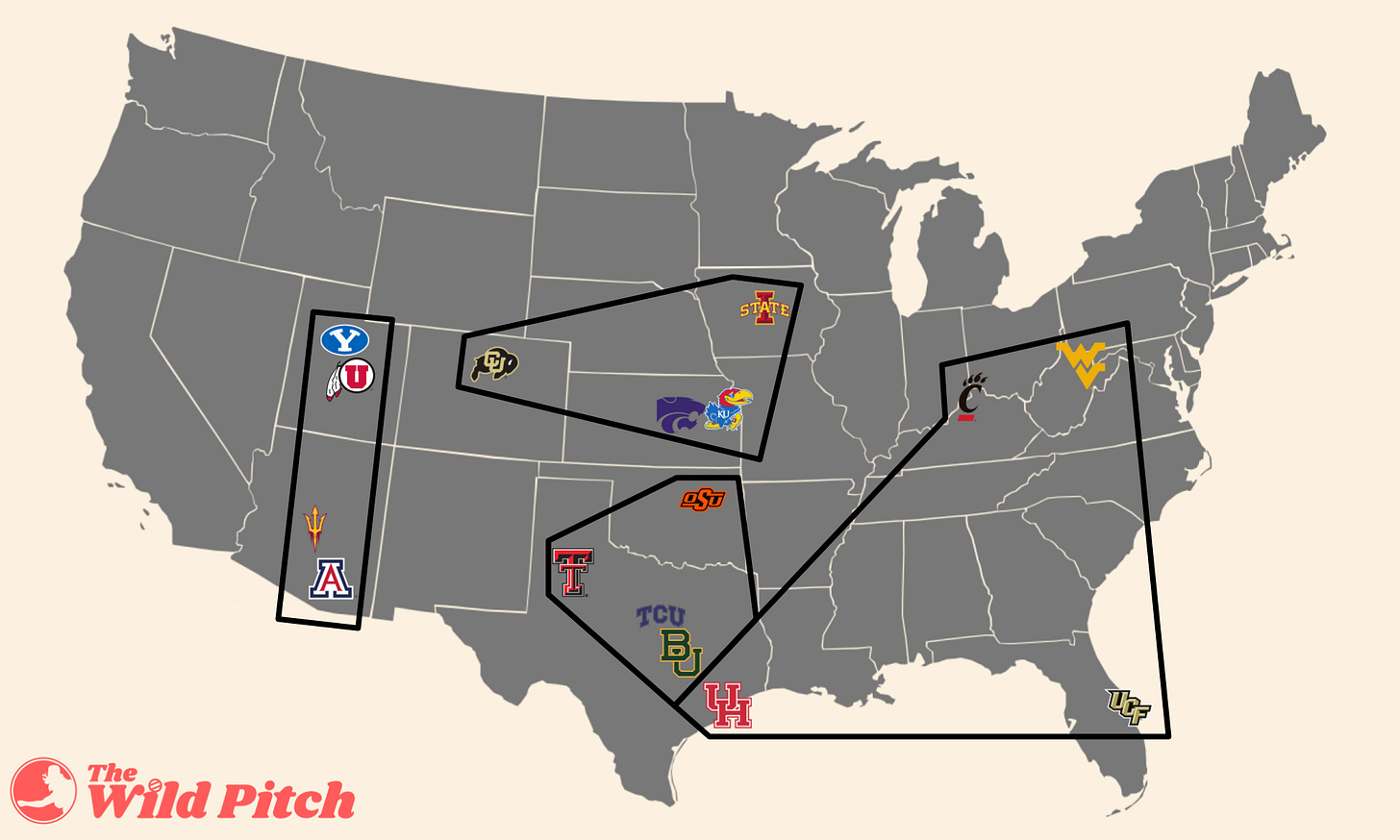

What helps the case for pods most, though, is that two natural arrangements immediately present themselves. Setting up the four westernmost teams is obvious as can be, and it seems clear that the trios of Colorado/Kansas/KSU, Tech/TCU/Baylor, and Cincinnati/WVU/UCF should end up together for further geographic efficiency. That leaves Oklahoma State, Houston, and Iowa State, which have two reasonable options. This is one, where the Cowboys go with their northern opponents and old Big 8 rival, the Cougars end up in an all-Texas pod, and the Cyclones stick with the easternmost teams. It’s a very tempting setup, especially with that hot-blooded south pod just begging to be put together, but there’s one glaring issue: no Farmageddon.

Fixing this requires shuffling the OSU/UH/ISU group around, leaving us with a little more travel and no Lone Star State pod, but otherwise a very strong alignment. Just about every single currently active rivalry between the Big XVI’s members is maintained in this setup, and while it doesn’t directly add a lot of exciting new ones or old favorites, the schedule will still bring those around every other year—more than fine for historical classics like Tech-Arizona and Utah-Colorado.

With any three-rival or four-team pod alignment, there’s an extra-fun option hidden in the schedule. The natural inclination is to go with the 3+6 setup that the SEC heavily considered before adopting its temporary 1+7 schedule (boo!), but you could instead play just one game against each other pod for a 3+3, giving you a full six weeks outside the conference slate to play with. Why do that? Well, you can devote four of them to a large OOC schedule, then clear the final two weeks of the season for an eight-team conference playoff. The best two teams in each pod would face off, the winners would meet during Rivalry Week, and the last pair left standing would duke it out for the conference championship and effective CFP autobid. Throw in some consolation games for other teams (e.g., #3s vs. #4s in Week 12, then #3s vs. #3s and #4s vs. #4s in cross-pod play for Week 13) and you’ve got a unique eight-game conference slate that puts the best games last.

Sacrilege? Sure. Washington is in the same conference as Rutgers now, keep up.

Divisions

Well, yes, this is technically a possibility. The thing is, even without cross-divisional rivalries (which are blessedly unnecessary thanks to how the geography lines up), a 16-team conference can only get its cross-divisional teams to play once every four years, which just doesn’t make sense when there are so many better options on the table.

Still, the idea will at least be bandied about within Big XVI boardrooms, and this is probably the proposal that should be taken most seriously. On account of most of the conference’s rivalries being between geographically close teams, the question here is more about which broader historical boundaries to preserve. Five of these teams were in the Pac-12 or, in BYU’s case, had close ties to it; eight of them were in the most recent incarnation of the Big 12; six of them were in the Big Eight; four of them were in the Southwest Conference; and three of them were in the Border Conference. Not all of those traditional ties can be preserved, but I’ve chosen here to put the former Pac-12 and SWC groups together and sort out the rest along geographic and rivalry lines. It’s important to note that basketball scheduling doesn’t have to follow the same rules as football, and using these broad groups might make more sense in that sport. Fourteen games against divisional opponents (two each) and four games against half of the opposite division is an easy route to eighteen conference games, and nobody misses out on much at all.

Chaos!

For decades, the NCAA has held conferences to a pretty firm, consistent ruleset when it comes to member counts and scheduling alignments. With the exception of the WAC’s brief experiment with pods during the 1990s, the only real options have been two divisions or one unified league. But in recent years, those rules have been relaxed somewhat, allowing increasingly cumbersome superconferences to navigate the complicated needs of their teams with a bit more freedom. In our case, that means we can come up with some pretty outlandish ideas that are at least hypothetically feasible…if it weren’t all but certain that the Big XVI would shoot them down before ever getting to the NCAA approval stage. People who get paid millions of dollars a year to make sure they don’t ruin everything are no fun, y’all.

Hey, I’m not kidding when I say things can get weird! Looking at a map of the Big XVI, two facts about UCF jump out at you: they lack vital historical ties with any particular team in the league, and they’re now the furthest-removed member geographically by a vast margin. So why not put the other fifteen teams in a trio of five-team pods—which happens to be a really nice number, capturing almost every major rivalry and historical group—and have the Knights play an independent-style, cross-country schedule?

Here’s how it would work: every team plays four games within its pod and two against the other two pods, giving it an eight-game schedule. Then, three teams from each pod add a game against UCF, getting them and the Knights to nine games apiece. The remaining six play an additional game against each other, getting everybody to the same schedule length. The main practical problem is ensuring those additional cross-pod games never conflict with the two cross-pod games already included, but it’s not impossible. Aside from that, the question of who makes the title game can be resolved in a number of ways—if the conference is crazy enough to do this, it could probably take a page out of the WCC’s book and get the sport’s resident statistical genius (Bill Connelly, in this case) to create a system that picks the best teams based on their strength of record.

Obviously, though, any sliver of a chance this alignment has of becoming reality rests solely on UCF’s shoulders. The Big XVI would certainly need to strike some sort of deal accommodating the additional travel this system would require, but the Knights would have to decide if having something akin to Notre Dame’s scheduling arrangement with the ACC is right for their program. If they’re game for it, though, there might not be a better setup for keeping all the best games annual without requiring weird locked-in rivalries that don’t make sense.

Then again, ask yourself: do we even need alignment? The Big XVI is full of teams that have so many differing priorities that a one-size-fits-all system just doesn’t seem quite right. Why not simply let them pick their own schedules, reaching agreements with each other as they do for non-conference games? The league could freely choose whether eight or nine games would be best, tell teams to spend, say, February settling which opponents they would face that year, and let them have at it.

OOC is, after all, the best-scheduled part of the sport right now. It’s a solid mix of buy games against weaker opponents that still pull the occasional upset, as well as stronger matchups with rivals, geographic neighbors, and evenly-matched opponents. It’s a rare case where programs don’t need to be too heavily incentivized to do what’s best for them and for their conference—and a SOR-based standings table would help ensure they’re not averse to playing a strong schedule.

Rivalries might still be skipped on occasion, but that arguably just adds to the appeal of this system. Teams wouldn’t be avoiding rivals for any financial gain or program stability; they would, instead, do it purely out of spite or cowardice, the perfect ingredients to create a matchup brimming with narrative when the game in question returns. We’ve seen this happen in dramatic fashion during non-conference games, too—why not in league play?

In conclusion…

…yeah, this still sucks.

The Big XVI is, in a vacuum, pretty exciting to me as a football fan. It’s a really neat group of teams, and if the alternative was programs like Houston, BYU, and Utah being left out in the cold while the power conferences contracted even further, this wasn’t the worst way for things to shake out. There’s little doubt, though, that fans of almost every team here (aside from the newly-promoted trio from the AAC) would rather have stuck with the old conference alignment that paired them with closer rivals and had another fun conference nearby to check in on from time to time. One of the worst consequences of realignment is the fact that fans of the Big 12 and Pac-12, two really enjoyable leagues with chaos that the SEC, ACC, and Big Ten generally lack, ended up on opposite sides of a struggle for survival.

Nevertheless, there are some things to like about the direction college football is heading, amid the myriad reasons to hate it. The twelve-team playoff is exciting, and the NIL/transfer era has given unprecedented value to the voices and talents of individual players. The negative consequences of these changes are looming, and there are sure to be some, but on the whole they seem like positive moves for a sport that’s otherwise trying to shoot itself in the foot.

The Big XVI is a microcosm of what college football has become. It is, indeed, a shell of its former self in some ways, a conference lacking geographical or traditional cohesion between its furthest-flung members, and one that effectively cut a dying league in half to save itself and secure its future for a few more years. But there are still reasons to watch, because as much history as these programs might lack, the pure parity and excitement of the league is going to be thrilling. There’s no clear frontrunner in this conference, a league lacking any of college football’s old blood but holding so much of the new, and no matter what alignment it settles on, it’s going to be must-watch stuff.

I hope we can find a 3-6-6 formulation that nobody truly hates.

The biggest thing I've hated about the 14 team SEC was its insistence on divisions, which has led to the hilariously sad fact that Georgia has not yet played at Texas A&M.

I think my attempts on CFBcord have managed to hit the mark, but in the end, this does suck in some way. I'm certainly excited as a West Virginia fan to watch us play in new & exciting locations, but the cost is significant.